Editor’s note: This post was originally published June 20th, 2025.

What is the Sky View Factor and why does it matter in our cities?

I’m back with another sunny, summer-inspired geospatial adventure!

Ever wonder how much sky you can actually see when you’re standing on a busy city street or under a cluster of city trees? That visible slice of sky called the Sky View Factor (SVF) has a surprisingly big say in how cities heat up, cool down, and even how comfortable we feel outside. The less sky you see, the more heat gets trapped between buildings and trees, creating those urban heat islands, where city temperatures climb higher than surrounding areas. These heat islands don’t just make summer days unbearable, they can worsen air pollution, increase energy demand for cooling, strain public health by amplifying heat-related illnesses, and even accelerate the wear and tear on city infrastructure.

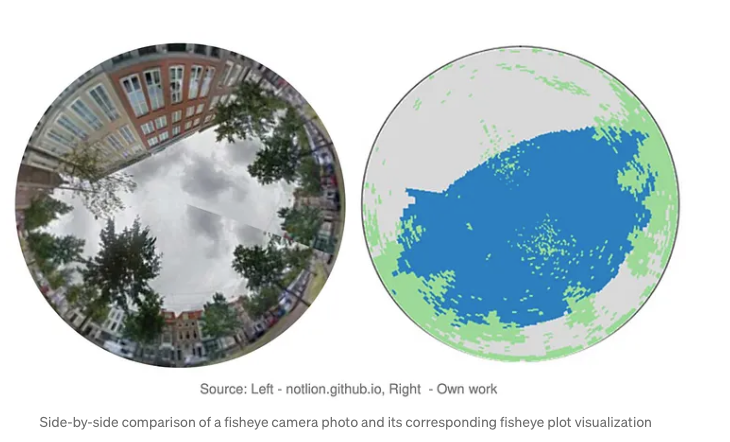

Measuring SVF takes more than just a weather app or a quick satellite snapshot, you need a detailed, 3D, street-level view of the city. That’s where LiDAR point cloud data shines, capturing billions of laser-scanned points from every rooftop, treetop, street, and sidewalk. This treasure trove of 3D data lets us model the urban canopy, the intricate layer of buildings and greenery that controls how sunlight and air flow through the cityscape. From this, we can calculate SVF and generate cool fisheye plots that show exactly how much sky you’d see lying anywhere on the ground.

Back in my master’s program, some classmates and I built an app for the municipality of The Hague that let users click on a map or upload a list of points to get SVF values and how much the sky is blocked by buildings and trees. You can check out our full report with the front-end and backend code here. Back then, we ran the calculations using NumPy arrays and plenty of good old-fashioned for-loops. I’m now reworking the project using PySpark, with a focus on scalable, data warehousing for big data analytics rather than real-time, on-the-fly processing, without delving deeply into the underlying mathematical computations. That’s where Databricks shines: its cloud-native platform effortlessly handles massive LiDAR datasets, turning mountains of 3D points into quick, actionable insights. Whether you’re a city planner aiming to cool down urban streets or simply a curious urban data explorer, it’s never been easier or more fun to look up and ask: how much sky do we really see?

Implementation:

The following implementation is part of the training we offer at RevoData focused specifically on leveraging the geospatial capabilities of Databricks.

In this implementation, I want to focus on code refactoring and explore the options available to start with the low-hanging fruit, highlighting which parts of the code can be adapted for distributed processing with minimal changes.

Let’s get started!

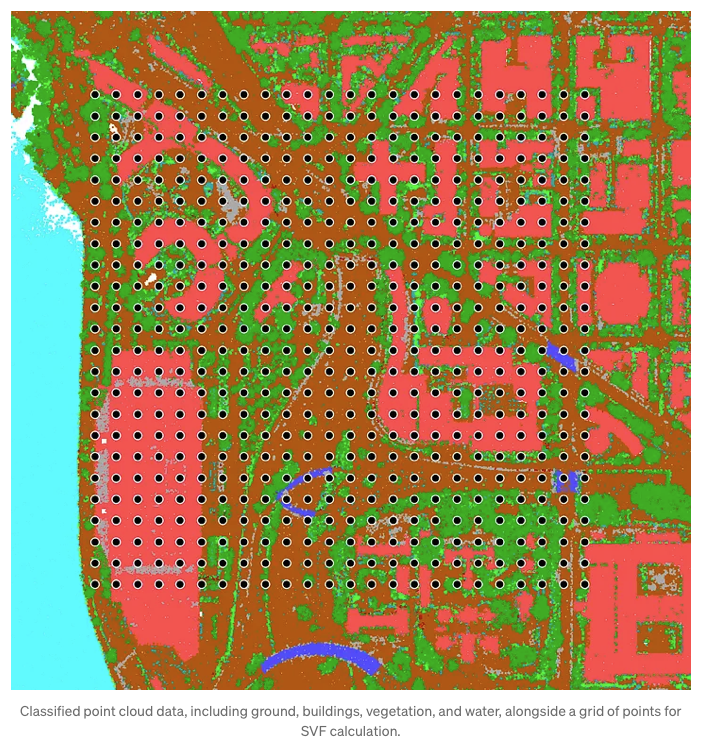

Datasets

As I mentioned earlier, we originally used point cloud data from the City of The Hague for this project. But today, I’m taking you to Washington, partly to switch up the scenery for myself, and partly so you can download the data more easily from an English-language website. The data is fully available here. I also generated a grid of 576 points across the area, which we’ll use to calculate the Sky View Factor (SVF).

Import libraries

In this implementation, we need couple of libraries which I import in one go:

import math

import numpy as np

import boto3

import os

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import pdal

import json

import io

import pyarrow as pa

from pyspark.sql.functions import col, sqrt, pow, lit, when, atan2, degrees, floor

from pyspark.sql.types import StructType, StructField, DoubleType, FloatType, IntegerType, ShortType, LongType, ByteType, BooleanType, MapType, StringType, ArrayType

import pandas as pd

from sedona.spark import *

from pyspark.sql import functions as F

from pyspark.sql.window import Window

import base64

from PIL import Image

Data ingestion

For the generated grid points, Apache Sedona makes geospatial data ingestion remarkably easy.

config = SedonaContext.builder() .\

config('spark.jars.packages',

'org.apache.sedona:sedona-spark-shaded-3.3_2.12:1.7.1,'

'org.datasyslab:geotools-wrapper:1.7.1-28.5'). \

getOrCreate()

sedona = SedonaContext.create(config)

# The path to the grid geopackage and point cloud las file

dataset_bucket_name = "revodata-databricks-geospatial"

dataset_input_dir="geospatial-dataset/point-cloud/washington"

gpkg_file = "grid/pc_grid.gpkg"

pointcloud_file = "las-laz/1816.las"

input_path = f"s3://{dataset_bucket_name}/{dataset_input_dir}/{pointcloud_file}"

# Read the grid data

df_grid = sedona.read.format("geopackage").option("tableName", "grid").load(f"s3://{dataset_bucket_name}/{dataset_input_dir}/{gpkg_file}").withColumnRenamed("geom", "geometry").withColumn("x1", F.expr("ST_X(geometry)")).withColumn("y1", F.expr("ST_Y(geometry)")).select("fid", "x1", "y1", "geometry")

num_partitions = math.ceil(df_grid.count()/2)

To ingest point cloud data, we can use libraries like laspy or PDAL. In this case, I used PDAL, applying a few read-time optimizations to efficiently convert the output array into a PySpark DataFrame:

def _create_arrow_schema_from_pdal(pdal_array):

"""Create Arrow schema from PDAL array structure."""

fields = []

# Map PDAL types to Arrow types

type_mapping = {

'float32': pa.float32(),

'float64': pa.float64(),

'int32': pa.int32(),

'int16': pa.int16(),

'uint8': pa.uint8(),

'uint16': pa.uint16(),

'uint32': pa.uint32()

}

for field_name in pdal_array.dtype.names:

field_type = pdal_array[field_name].dtype

arrow_type = type_mapping.get(str(field_type), pa.float32()) # default to float32

fields.append((field_name, arrow_type))

return pa.schema(fields)

def _create_spark_schema(arrow_schema):

"""Convert PyArrow schema to Spark DataFrame schema."""

spark_fields = []

type_mapping = {

pa.float32(): FloatType(),

pa.float64(): DoubleType(),

pa.int32(): IntegerType(),

pa.int16(): ShortType(),

pa.int8(): ByteType(),

pa.uint8(): ByteType(),

pa.uint16(): IntegerType(), # Spark doesn't have unsigned types

pa.uint32(): LongType(), # Spark doesn't have unsigned types

pa.string(): StringType(),

# Add other type mappings as needed

}

for field in arrow_schema:

arrow_type = field.type

spark_type = type_mapping.get(arrow_type, StringType()) # default to StringType

spark_fields.append(

StructField(field.name, spark_type, nullable=True)

)

return StructType(spark_fields)

def pdal_to_spark_dataframe_large(pipeline_config, spark, chunk_size=1000000):

"""Streaming version for very large files."""

pipeline = pdal.Pipeline(json.dumps(pipeline_config))

pipeline.execute()

# Get schema from first array

first_array = pipeline.arrays[0]

schema = _create_arrow_schema_from_pdal(first_array)

# Create empty RDD

rdd = spark.sparkContext.emptyRDD()

# Process arrays in chunks

for array in pipeline.arrays:

for i in range(0, len(array), chunk_size):

chunk = array[i:i+chunk_size]

data_dict = {name: chunk[name] for name in chunk.dtype.names}

arrow_table = pa.Table.from_pydict(data_dict, schema=schema)

pdf = arrow_table.to_pandas()

chunk_rdd = spark.sparkContext.parallelize(pdf.to_dict('records'))

rdd = rdd.union(chunk_rdd)

# Convert to DataFrame

return spark.createDataFrame(rdd, schema=_create_spark_schema(schema))

pipeline_config = {

"pipeline": [

{

"type": "readers.las",

"filename": input_path,

}

]

}

# Convert point cloud array to Spark DataFrame

df_pc = pdal_to_spark_dataframe_large(pipeline_config, spark)

df_pc = df_pc.withColumn("geometry", F.expr("ST_Point(X, Y)"))

df_pc.write.mode("overwrite").saveAsTable(f"geospatial.pointcloud.wasahington_pc")

Identifying point cloud data surrounding each grid point

Next, we need to retrieve all point cloud data within 100 meters for buildings and high vegetation, these are used for SVF calculation. For ground points, we only consider those within 10 meters, as they’re used solely to estimate the elevation of each grid point.

df_selected = df_pc.select("X", "Y", "Z", "Classification")

dome_radius = 100

height_radius = 10

# Register as temp views

df_pc.createOrReplaceTempView("pc_vw")

df_grid.createOrReplaceTempView("grid_vw")

# Perform spatial join using ST_DWithin with 100 meters

grid_join_pc = spark.sql(f"""

SELECT

g.fid,

ST_X(g.geometry) AS x1,

ST_Y(g.geometry) AS y1,

p.classification,

p.x AS pc_x,

p.y AS pc_y,

p.z AS pc_z,

ST_Distance(g.geometry, p.geometry) AS distance,

g.geometry AS g_geometry,

p.geometry AS pc_geometry

FROM grid_vw g

JOIN pc_vw p

ON ST_DWithin(g.geometry, p.geometry, {dome_radius})

WHERE p.classification IN (5, 6) OR (p.classification = 2 AND ST_DWithin(g.geometry, p.geometry, {height_radius}))

""")

Estimating grid point elevation from nearby point cloud data (10m Radius)

Here, we determine the elevation of each grid point by identifying its dominant surrounding class, either building or ground, and then computing the average elevation of that class within a defined radius.

# Filter only classification 2 and 6 and count occurrences of (fid, classification)

grouped = grid_join_pc.filter(

(F.col("classification").isin(2, 6)) & (F.col("distance") <= height_radius)

).groupBy("fid", "classification").count()

# Define window: partition by fid, order by count descending

window_spec = Window.partitionBy("fid").orderBy(F.desc("count"))

# Apply row_number

ranked = grouped.withColumn("rn", F.row_number().over(window_spec))

# Compute the average elevation for each grid point using nearby point cloud data within a specified radius.

grid_pc_elevation = grid_join_pc.join(g_classification_df, on=["fid", "classification"]).filter(

(F.col("distance") <= height_radius)

).groupBy("fid").agg(

(F.sum("pc_z") / F.count("pc_z")).alias("height")

)

# Combine point cloud data with classification info and computed height, optimized with repartitioning.

grid_pc_elevation_all = grid_join_pc.withColumnRenamed("classification", "p_classification").join(g_classification_df, on=["fid"]).join(grid_pc_elevation, on=["fid"]).repartitionByRange(num_partitions, "fid")

# Filter out ground points (e.g., class 2) to retain only buildings and high vegetation points for analysis.

grid_pc_cleaned = grid_pc_elevation_all.filter("p_classification != 2").repartitionByRange(num_partitions, "fid")

Creating the dome, generating the plot, and calculating the SVF

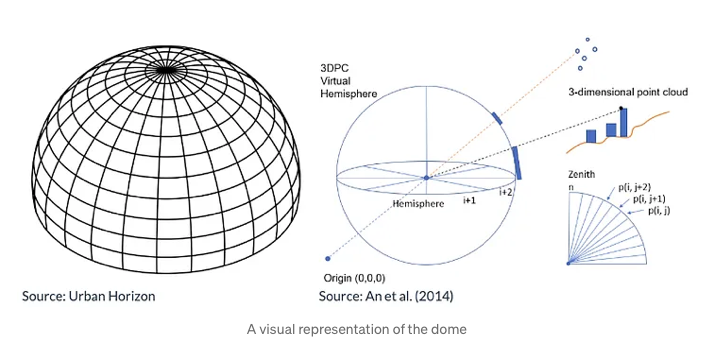

The dome is a representation of the sky, going from the horizon all the way to the zenith (directly on top) of the viewpoint. The dome can be split into sectors based on horizontal and vertical directions, in essence creating a dome-like shaped grid. The units used to split the sectors are 2 degrees horizontally (azimuth angle), and 1 degree vertically (elevation angle), which are considered as appropriate values for calculation.

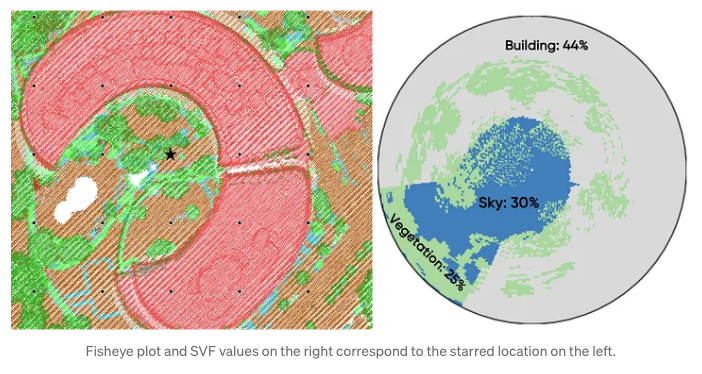

To calculate the Sky View Factor (SVF), point cloud data is projected onto a dome divided into sectors, marking which sectors are blocked from view. The closest point in each sector determines the obstruction, and if that point is a building, all sectors below it in that direction are also considered blocked. The unobstructed proportion of the dome’s area gives the SVF. For clarity, the results are visualized in a circular plot showing which sectors are clear sky or obstructed by buildings or vegetation, oriented to the north for easy interpretation.

# Calculate raw azimuth angle (in degrees) from each grid point to each point in the point cloud.

# Shifted by -90 to align with the 0° direction being north.

grid_pc_az = grid_pc_cleaned.withColumn(

"azimuth_raw",

degrees(F.atan2(F.col("pc_y") - F.col("y1"), F.col("pc_x") - F.col("x1"))) - 90

)

# Normalize azimuth angle to fall within the range [0, 360).

grid_pc_az = grid_pc_az.withColumn(

"azimuth",

when(F.col("azimuth_raw") < 0, F.col("azimuth_raw") + 360).otherwise(F.col("azimuth_raw"))

)

# Drop the temporary azimuth_raw column to clean up the DataFrame.

grid_pc_az = grid_pc_az.drop("azimuth_raw")

# Calculate the elevation angle (in degrees) from the grid point to each point in the point cloud.

# Height is divided by 1000 to convert from millimeters to meters if necessary.

grid_pc_az = grid_pc_az.withColumn(

"elevation",

degrees(F.atan2(F.col("pc_z") - F.col("height") / 1000, F.col("distance")))

)

# Bin azimuth angles into 2-degree intervals (0–179 bins for 360°).

grid_pc_az = grid_pc_az.withColumn("azimuth_bin", F.floor(F.col("azimuth") / 2))

# Get the minimum elevation angle across all records to define the lower bound of elevation bins.

min_val = F.lit(grid_pc_az.select(F.min("elevation")).first()[0])

# Get the maximum elevation angle across all records to define the upper bound of elevation bins.

max_val = F.lit(grid_pc_az.select(F.max("elevation")).first()[0])

# Compute bin width by dividing elevation range into 89 equal parts (90 bins total).

bin_width = (max_val - min_val) / 89

# Bin elevation angles into 90 intervals, ensuring they stay within the [0, 89] range.

grid_pc_az = grid_pc_az.withColumn("elevation_bin",

F.least(

F.greatest(

F.floor(

(F.col("elevation") - F.lit(min_val)) /

F.lit((max_val - min_val)/90)

).cast("int"),

F.lit(0) # Clamp minimum bin index to 0

),

F.lit(89) # Clamp maximum bin index to 89

)

)

# Define a window that partitions the data by azimuth and elevation bins,

# and orders points within each bin by their distance to the grid point.

window_spec = Window.partitionBy("azimuth_bin", "elevation_bin").orderBy("distance")

# Assign a row number within each azimuth-elevation bin, so the closest point (smallest distance) gets rank 1.

df_with_rank = grid_pc_az.withColumn("rn", F.row_number().over(window_spec))

# Keep only the closest point (rank 1) in each bin and drop the temporary rank column.

# Then repartition the result by 'fid' to optimize parallel processing in subsequent steps.

closest_points = df_with_rank.filter(col("rn") == 1).drop("rn").repartitionByRange(num_partitions, "fid")

def create_dome(pdf: pd.DataFrame, max_azimuth: int = 180, max_elevation: int = 90) -> np.ndarray:

"""

Creates a dome matrix based on azimuth and elevation bins, with obstruction handling for buildings.

"""

dome = np.zeros((max_azimuth, max_elevation), dtype=int)

domeDists = np.zeros((max_azimuth, max_elevation), dtype=float)

for _, row in pdf.iterrows():

a = int(row["azimuth_bin"])

e = int(row["elevation_bin"])

dome[a, e] = row["p_classification"]

domeDists[a, e] = row["distance"]

# Mark parts of the dome that are obstructed by buildings

if np.any(dome == 6): # 6 = buildings

bhor, bver = np.where(dome == 6)

builds = np.stack((bhor, bver), axis=-1)

shape = (builds.shape[0] + 1, builds.shape[1])

builds = np.append(builds, (bhor[0], bver[0])).reshape(shape)

azimuth_change = builds[:, 0][:-1] != builds[:, 0][1:]

keep = np.where(azimuth_change)

roof_rows, roof_cols = builds[keep][:, 0], builds[keep][:, 1]

for roof_row, roof_col in zip(roof_rows, roof_cols):

condition = np.where(np.logical_or(

domeDists[roof_row, :roof_col] > domeDists[roof_row, roof_col],

dome[roof_row, :roof_col] == 0

))

dome[roof_row, :roof_col][condition] = 6

return dome

# Plot dome

def generate_plot_image(dome):

# Create circular grid

theta = np.linspace(0, 2*np.pi, 180, endpoint=False)

radius = np.linspace(0, 90, 90)

theta_grid, radius_grid = np.meshgrid(theta, radius)

Z = dome.copy().astype(float)

Z = Z.T[::-1, :] # Transpose and flip vertically

Z[Z == 0] = 0

Z[np.isin(Z, [5])] = 0.5

Z[Z == 6] = 1

if Z[Z == 6].size == 0:

Z[0, 0] = 1 # Force plot to show something

fig = plt.figure(figsize=(4, 4))

ax = fig.add_subplot(111, projection='polar')

cmap = plt.get_cmap('tab20c')

ax.pcolormesh(theta, radius, Z, cmap=cmap)

ax.set_ylim([0, 90])

ax.tick_params(labelleft=False)

ax.set_theta_zero_location("N")

ax.set_xticks([])

ax.set_yticks([])

buf = io.BytesIO()

plt.savefig(buf, format='png', bbox_inches='tight', pad_inches=0)

plt.close(fig)

buf.seek(0)

img_base64 = base64.b64encode(buf.read()).decode('utf-8')

return img_base64

def process_and_plot(pdf: pd.DataFrame) -> pd.DataFrame:

fid = pdf["fid"].iloc[0]

# Create dome with building/vegetation obstruction

dome = create_dome(pdf)

# Generate base64-encoded fisheye plot image

plot_base64 = generate_plot_image(dome)

# Compute SVF and obstruction metrics

SVF, tree_percentage, build_percentage = calculate_SVF(100, dome)

return pd.DataFrame(

[[fid, dome.tolist(), plot_base64, SVF, tree_percentage, build_percentage]],

columns=["fid", "dome", "plot", "SVF", "treeObstruction", "buildObstruction"]

)

Results

As you can see in the code above, some parts still rely on NumPy structures for operations like dome construction, plotting and SVF calculation. Since each grid point corresponds to a single dome, we can safely apply these NumPy-based functions on a per-row basis. To do this efficiently in PySpark , without too much code refactoring, I use the applyInPandas method. This allows us to apply our existing Pandas-based logic directly to each group of rows (grouped by the "fid" column) within the PySpark DataFrame. This way, we can leverage distributed processing in Spark while reusing existing, well-tested NumPy code for the dome and SVF calculations.

# Desired schema

output_schema = StructType([

StructField("fid", IntegerType()),

StructField("dome", ArrayType(ArrayType(IntegerType()))),

StructField("plot", StringType()),

StructField("SVF", FloatType()),

StructField("treeObstruction", FloatType()),

StructField("buildObstruction", FloatType())

])

result_df = closest_points.groupBy("fid").applyInPandas(process_and_plot, schema=output_schema)

result_df.write.mode("overwrite").saveAsTable(f"geospatial.pointcloud.wasahington_grid")

# Fetch the the grid point with fid = 105 for a sample visualization

pdf = result_df.filter("fid = 105").select("fid", "plot").toPandas()

for index, row in pdf.iterrows():

# Decode base64 string to bytes

img_bytes = base64.b64decode(img_base64)

# Load image with PIL

image = Image.open(io.BytesIO(img_bytes))

# Display using matplotlib (preserves original colors)

plt.figure(figsize=(6, 6))

plt.imshow(image)

plt.axis('off') # Hide axes

plt.show()

What is next?

In our live training “Databricks Geospatial in a Day” at RevoData Office, we’ll delve deeper into the logic behind this code and use this example to demonstrate how to:

- Set up a cluster capable of processing point cloud data

- Visualize LiDAR point clouds directly in Databricks

- Efficiently partition point cloud data for distributed processing

- Tackle the challenges of code migration and minimal refactoring

Go ahead and grab your spot for the training using the link below, can’t wait to see you there!

https://revodata.nl/databricks-geospatial-in-a-day/

Melika Sajadian

Senior Geospatial Consultant at RevoData, sharing with you her knowledge about Databricks Geospatial